So Snapchat has turned down an offer of three billion dollars from Mark Zuckerberg.[1]

The first thing that came to mind when I read this was something interesting David Sacks said last year, during an interesting rant on Facebook which turned into a discussion with Marc Andreessen about the defensibility of technology businesses. Unfortunately Sacks made headlines for saying that Silicon Valley was ‘over as we know it’ and that ‘there would be no more billion dollar companies’, when what he said was far more nuanced:

If tech companies are constantly being disrupted, why are they valuable in the first place? If even the big winners like Facebook and Salesforce are just an Instagram away from evisceration, then why invest in them? …

The bulls want their cake and to eat it too, believing markets can both be incredibly valuable and constantly disrupted. I’m not a bear, but I believe disruption happens in waves, then settles down into a more stable pattern, and that’s what makes incumbents valuable… more entrepreneurs seem to be focused on existing categories than creating new ones. [2]

The point is an interesting one – if technology companies are not defensible then they are not valuable. This is the first in a series of four posts where I look at this question of defensibility – this time focussing on network effects as a means of defending a technology business. There are three other means of defending a business, all of which I’ve lifted from Peter Thiel and will deal with in subsequent posts.[3]

What are network effects and how can they be destroyed?

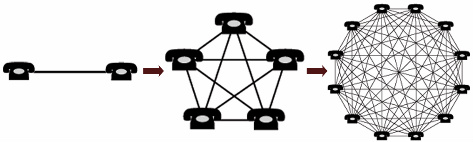

A ‘network effect’ describes the effect of having a business where the value lies inside its network. For example, if I were to clone Facebook tomorrow, nobody would go on it because the ‘network’ of my friends is on Facebook. However, I am of the view that not all network effects are created equal.

The problem of uneven topology

I think that to understand how a network effects business is vulnerable you need to look at it from the perspective of a market entrant. How would a savvy entrepreneur find a way to destroy this incumbent? To this end Chris Dixon provides a great analysis of the many ways to circumvent the chicken and egg problem in a startup (the key problem for starting any network business).[4] I would encourage you to read the article, but one thing I think is really important is this idea that:

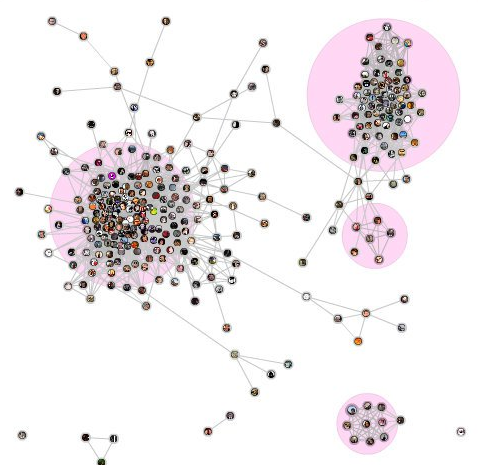

Real-life networks are often very different from the idealized, uniformly distributed networks pictured in economics textbooks. Facebook exploited the fact that social connections are highly clustered at colleges as a “beachhead” to challenge much bigger incumbents (Friendster). By finding clusters in the network smaller companies can reach critical mass within those sub-clusters and then expand beyond.

I can’t help but think that investors aren’t seeing this when analysing the size of network effects businesses. The defensibility of a network is proportionate to the regularity of its topology. In networks where the connections are evenly spread amongst nodes, the network is far more defensible than where connections cluster heavily. Think about a network as woven fabric – where the weave clumps together and leaves gaps, the fabric is easily torn apart; where the weave is symmetrical the fabric is highly durable.

Examples of the effect of clustered networks in social media incumbents

So, not all networks are created equal. On Facebook for example, users want to stay up to date with what their friends are doing. Once their friends move onto a separate network, they simply stop using Facebook. Contrast this with something like Twitter where users tend to follow a wide variety of content providers. My timeline is a mix of thinkers from technology, law (practical and academia) and business, together with a variety of news outlets, sports teams, and personal friends. Even if by some miracle one of these clusters were to vanish, the others would remain, and therein lies the strength of the Twitter network.

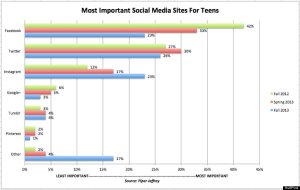

Facebook on the other hand has always had and will continue to suffer from the problem that the only network that exists is that of you and your ‘friends’, or, usually a group of about 50 friends that you care about the most. These are the people who keep you coming back to the website often. Unfortunately, it is very easy for these networks to move. One friend sends out a WhatsApp invitation to 50 people and within seconds the engagement has shifted onto WhatsApp. Or a person sends a snap to a dozen people on Snapchat. This is easy to start – in fact it was just like that that a group of my own Facebook friends shifted over onto Whatsapp about a month ago. But I won’t move from Twitter until Barack Obama, the Pope, Kanye West and the Guardian move too.A telling visual illustration of this is effect is the above graph which shows Facebook usage dropping off the face of the planet in favour of ‘Instagram’ and ‘Other’ (presumably Snapchat). Twitter’s network on the other hand seems pretty stable, as does Tumblr’s (both built on similar ideas of interest-based media and asynchronous following, rather than friend-based media and synchronous following). Facebook on the other hand appears to have dropped off the planet. I’m not sure how much we can read into this graph but it definitely fits my hypothesis around what makes something defensible. I would love to see some proper mathematical analysis of indicators like clustering coefficient etc on Twitter and Facebook, and whether those numbers correlate with long term user engagement.[6]

Defending the Social Media incumbents

1. Isolate defensible parts of the business from non-defensible parts

For starters, I think it is worth pointing out that just because the network effects of these products aren’t necessarily sustainable doesn’t mean that the businesses themselves aren’t. Of course, a business’ brand, proprietary technology and scale-cost advantages can also provide a great deal of defensibility.[3]

Large scale but non-defensible networks can modularise their businesses into defensible proprietary tech services like search, data analysis/machine learning, ad buying and serving, and infrastructure, and use this decoupled structure to launch a series of new products that are successful, not just clones of other products (as Facebook attempted with Facebook Camera (Instagram) and Facebook Poke (Snapchat)). Interesting examples of this are the big movie studios. They provide access to their campuses with a series of studio buildings, a centralised costume and set department, and access to finance and distribution, but other people produce the films.

2. Ascertain the degree to which the business is hit driven and invest accordingly

The dynamics of a social media platform can change drastically depending on the topology of the network – strong networks resemble AT&T before it was broken up, with a stranglehold on its customers, whereas weak networks resemble film companies.

When film companies discovered their vulnerability in the 1980s after a series of flops brought large studios to their knees, they joined or created media conglomerates, acquiring similar, less hit-exposed businesses to isolate the big losses of the movie business, providing enough capital to tide them over until the next big win. [7]

An example of a web company that failed to come to terms with being hit driven was Zynga – which was run like a technology company, when in reality it had more in common with Disney than it did with Facebook. The company was a constant saga of clones, creative acquisitions followed shortly after by sackings, and overall a culture that seemed to be in denial about the fact that its core defensibility was going to come from an ability to generate new hits rather than cloning or acquiring everything else that came along.

By now Facebook has become a behemoth of a corporation, but like Zynga and Yahoo it needs to adapt into an organisation that successfully launches a series of products that consumers love if it is going to remain defensible. Obviously its business is nowhere near as hit-driven as Zynga, but it is hit-driven nonetheless. Cloning threatening apps like Instagram and Snapchat is not a strategy that has worked in the past, nor will acquiring these companies for large sums of money work sustainably into the future. It needs to develop its own ability to generate new hits in an industry that increasingly seems to be hit-driven.

3. Change the network topology to be less reliant on small clusters

Facebook made a great move when it released its Google+ megaupdate – it introduced asynchronous following and in doing so really started to become more like Twitter, with users now getting updates from their favourite brands, thinkers and influencers. This update has really put a lot more relevant content in users’ streams and helped to hold the fort against new entrants, with consumers taking in a lot of content from large pages as well as from their friends. I now know people who only go onto Facebook to read their favourite updates from car enthusiast pages.

For a business like Snapchat, this is a hard one. The network is really focussed around close friends. But there could be some interesting new features that they come up with, like the ability to get snaps from celebrities. This might keep people engaged even if their friends leave the service, and provide a monetisation route as well.

Lessons for Investors

It is one thing when companies raise VC money to ignore issues of defensibility and focus on growth. But as these companies are now publicly listed, defensibility is a real issue. You can’t call yourself an investor if you’re not thinking about what Warren Buffett refers to as the ‘moat’ that defends a particular company. If a business claims to be defensible through ‘network effects’, its investors need to start asking questions, and realising that not all networks are created equal.

In the case of a business like Snapchat, whose network is highly clustered, network effects won’t provide defensibility once the novelty wears off. That said, network effects aren’t the only way to defend a business, and I’ll be interested to see how they fare in the long run. Certainly their short term growth has been impressive. In any event, it is never a good idea to bet against a passionate entrepreneur and I’m sure the founders will come up with lots of great new products and features in future.

I think the real issue here is with Facebook. I think if they are willing to spend 4 billion dollars in a single year to buy companies like Instagram and Snapchat, it shows that defensibility is a big problem for them. I’ll be interested to see what happens in future – their execs and investors need to really think twice about what line of business the company is in and how they’re going to defend it. Network effects certainly aren’t a silver bullet.

Interested by this post? Subscribe to get a copy of my posts as soon as they come out.

Footnotes

[1] http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2013/11/13/snapchat-spurned-3-billion-acquisition-offer-from-facebook/

[2] Ellipses added by me; http://www.businessinsider.com.au/david-sacks-silicon-valley-as-we-know-it-may-be-over-2012-8

[3] Love all of Peter’s class notes, a must read; http://blakemasters.com/post/21169325300/peter-thiels-cs183-startup-class-4-notes-essay

[4] This is a really, really good blog post; http://cdixon.org/2009/08/25/six-strategies-for-overcoming-chicken-and-egg-problems/

[5] Taken without permission, with apologies; http://jonathanstray.com/visualizing-communities

[6] There appears to be some limited analysis of clustering coefficient in social networks out there on the web. I’m not willing to go into this level of detail now though because clustering coefficient doesn’t directly describe the effect I am talking about (it is an indicator of it though). Also, the data is old and second hand. If I had a financial interest in figuring this out I would definitely devote the time to finding the most appropriate indicator for this and computing it.

[7] For more on this, go read Tim Wu’s ‘The Master Switch’ – it’s a really great book if you want to understand the history of big networks, media and technology; http://www.amazon.com/The-Master-Switch-Information-Empires/dp/0307390993